16th-Century Tapestries, Worst-Case Scenarios, and Intellectual Property

UK Research Trip Series

I recently returned from a 10-day research trip to the UK, where I was gathering material for three upcoming novels. In both my work as a historical romance author and a technical communicator, my job is the same: explaining complicated things to people and getting people to care about complicated things. Whether you’re an engineer, a history lover, a romance reader, or some glorious combination of all three, this series is for you.

I didn’t go to England to look at tapestries.

My research trip was scheduled down to the half hour, every day packed with visits to breweries, archaeological sites, country estates, monastic abbey ruins, and the London dockyards. (“My spreadsheets have spreadsheets,” I joked more than once.)

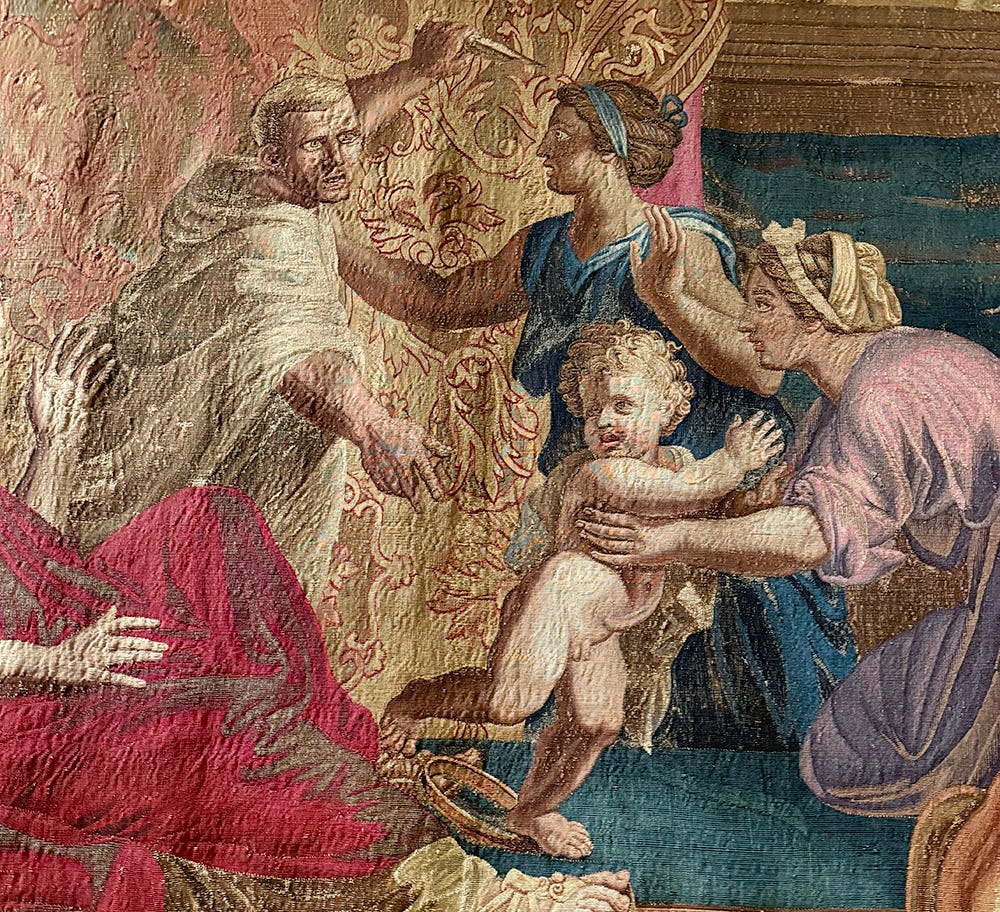

But along the way, I got an unexpected gift: the chance to see a dozen ancient European tapestries up close. From the Victoria and Albert Museum in London to Canons Ashby in Northamptonshire and the historic halls of Sudeley Castle on the outskirts of the Cotswolds, these woven works of art stopped me in my tracks.

I love tapestries. I love that they were crafted to be beautiful, to tell stories, and to still meet very human needs. They recorded histories, proclaimed alliances, and united generations. They were created by hands that understood how each stitch contributed to the whole.

Somewhere between admiring their artistry and reflecting on their purpose, I started to wonder: What’s our version of a tapestry today?

Why Tapestries?

Europe’s ancient tapestries are time machines. To fully appreciate them, you have to look at them through the lens of history.

Tapestries as Warmth

Climatologists refer to the epoch between the 1300s and 1850s as the Little Ice Age. The climate shift was global in scale and launched modern society. (Check out my Curious & Captivated section at the end if you want to read more.)

During these frigid centuries, the stone castles inhabited by society’s elite were particularly nippy. The primary purpose of tapestries was purely pragmatic: warmth.

Great, life-sized tapestries made of wool and silk helped to insulate a cold room in a stone keep. They lined walls, served as bed hangings, and covered unglazed windows.

Tapestries as Status Symbols

During late Medieval Europe and even through the 18th century, tapestries were often more valued than paintings. These works of art might tell a biblical story, recreate a local or ancient myth, record history and heraldry, declare allegiance to the monarch, or simply show idyllic scenes of pastoral life.

In the Middle Ages, a nobleman would travel with his tapestries – the ultimate display of Medieval street cred. So valued, tapestries were a spoil of war. To the victor goes the…wall hangings.

It’s important to understand that the value of tapestries went beyond intangible worth. Interwoven with vibrant wool and silk were threads of precious metal. This notion leads me to my main thought for today:

Tapestries as Mobile Wealth

Proof of generational prestige and threaded with gold and silver, tapestries didn’t just signify wealth, they were wealth. Or as my financial planning friends would say, tapestries were at once liquid and fixed assets. These were valued inheritances and coveted dowries.

Unlike paintings, tapestries could be folded and easily transported. In a pinch, they could even survive a bit of dampness. That made tapestries an ace in the hole – insurance against the worst-case scenario. The one possession you grabbed if your house was on fire.

Or as this article from Town and Country says:

In some respects, such tapestries were a literal store of wealth or, as Adamson puts it, “a tremendous amount of value condensed into a single object.” In times of crisis, these tapestries were often taken apart for their materials. “The reason we’ve lost a lot of them,” he adds, “is because they were melted down for the gold and silver—which gets across just how much metal there was in them.”

To take a many-century leap into early-00s pop culture, tapestries were the equivalent of the Bluth patriarch clicking his tongue and saying: “There’s always money in the banana stand.”

Today’s Tapestries

Taking in these works of art from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, my mind inevitably landed on the notion of tapestries as mobile wealth and their role as insurance against the storms of life. As an author of historical romance and a communicator specializing in engineering, technology, finance, and medicine, these are the brackish waters where I thrive.

It got me thinking: What are today’s tapestries? When all else is lost, what do we have to barter or sell?

What is my greatest asset? And what is yours?

I thought back to getting laid off last year. My husband is a teacher, so I didn’t exactly work for funsies. The first expense we cut was our elementary-aged boys’ after-school daycare. Meant to be temporary until I found a new job, it quickly became clear that our eight-year-old with dyslexia thrived in this new routine of coming straight home after school. His brilliant, beautiful brain needed a few hours to rest after doing hard things all day long.

What was a game changer in the best way for him was a worst-case scenario for the family budget.

I looked around, and with no 16th-century tapestries to melt down, I turned to what I know, to the skills I have with value, and I started Serif+Sway.

I think today’s tapestry – our mobile wealth, our ace in the hole – is intellectual property.

By intellectual property, I don’t just mean the industrial exponents – the patents and trademarks that make our society run. I’m also talking about the deeply personal kind: the knowledge you’ve earned, the instincts you’ve honed, the strange little zone of genius you’ve carved out in your corner of the world.

In today’s world, it’s no longer simply “What do I have?” but “What do I know?”

When I lost my job, I didn’t have gold-threaded wall hangings to pawn. But I had something I’d spent 15 years weaving: my ability to turn complex ideas into clarity and connection. That was enough to start Serif+Sway.

In moments of upheaval, our intellectual property – our creative fire, our work, our experience – is a tangible, practical, valuable thing. Like the tapestries of old, it can be folded up and carried with us wherever we go. It will survive a storm.

So I’ll ask again: What’s your tapestry? What could you unfurl when everything else is gone and say: “Here, I made this. Here, I know this. This has value.”

Because that just might be the thread that sees you through.

For the Curious & Captivated

Thanks for joining along. I’ll see you next time to talk about archeology.

I love this! 🙌